Why Small-Scale Fishers in Indonesia Need More Protection – And How We Can Help

Indonesia is one of the world’s largest producers of octopus, with Sulawesi waters contributing around 50% of the country’s total octopus production. The fishery is predominantly small-scale and artisanal, relying on traditional fishing methods such as handline and spear. Fishers operate small vessels under 1 Gross Tonnage (GT), and in some cases, they do not use vessels at all, instead gleaning for octopus along the shoreline during low tide. This fishery plays a vital role in the livelihoods of coastal communities across Wakatobi, Selayar, Banggai Laut, Luwuk, and Tojo Una-Una Regencies in Sulawesi waters.

Collaborative Efforts for Sustainable Solutions

Although the octopus fishery plays a significant role in Indonesia’s seafood industry, it largely operates informally, posing challenges for many fishers in terms of legal recognition, sustainability, and access to social security. The lack of proper registration and regulatory oversight have hindered opportunities for small-scale fishers to benefit from government support programs and long-term resource management initiatives. Promoting the sustainability of this fishery calls for collaborative efforts among government agencies, NGOs, and local communities to enhance governance, safeguard fishers’ rights, and integrate them into national protection frameworks.

In 2024, Pesisir Lestari (YPL) with the Octopus FIP – Consortium NGOs in Sulawesi – Indonesia conducted Social Responsibility Assessment (SRA) to look into the working conditions of these small-scale fishers. SRA serves as a complement to FIP to determine the extent of social risk in fisheries activities. The assessment identified that while there are no major findings in social risks related to forced labor, child labor, or human trafficking, the sector still faces challenges in terms of outreach and access to social protection. Many fishers operate small, unregistered vessels (under 1 Gross Tonnage), which potentially hamper their ability to obtain official recognition, fisheries subsidies and financial support.

This is certainly in line with the principles of the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency, which emphasizes the importance of clear information and vessel registration as a form of openness and legal assurance for fishers and fisheries actors (Principle 1), and how this can contribute to strengthening their representation in inclusive policy-making processes, including the provision of various forms of support that reinforce the position of fishers, especially small-scale fishers (Principle 9).

“Most fishers understand their basic rights, like the freedom to organize and sell their catch independently. But there are still major gaps in knowledge, many don’t know how to file complaints, register their boats, or access and utilize health and employment insurance provided by the government. We need an approach that goes beyond echoing fishers capacity; one that actively involves fishers in policy planning and decision-making. Strengthening collaboration between fisher groups and the government is the key to ensuring both recognition and empowerment,” stated Faridz Fachri, Program Manager, Pesisir Lestari (YPL).

Small-scale fishers operate in an unpredictable environment, where factors such as adverse weather conditions, fluctuating octopus populations, and market price declines can lead to unstable earnings. Unfortunately, they have limited access to comprehensive social security measures, including informal employment insurance, accident coverage, and pension schemes. While informal community-based support systems exist, there remains a significant need for institutional mechanisms to ensure their long-term security and well-being.

To address these concerns, Pesisir Lestari (YPL) and partners brought together key stakeholders, including government agencies, non-governmental organizations, academics, private sectors and community representatives into a discussion via a webinar event on December, 16th, 2024. The discussions aimed to enhance understanding of the importance of social security for small-scale fishers and explore collaborative solutions to improve their access to safety nets.

Participants of the Human Rights and Social Responsibility Policy Training, Central Sulawesi

Participants of the Human Rights and Social Responsibility Policy Training, Central Sulawesi

“Actually, we have been working to connect small-scale fishers with the national employment insurance system through BPJS, and the response has been quite positive. However, our coverage remains limited due to the challenging access, given Indonesia’s vast archipelagic geography. Cross-sector collaboration is truly needed,“ said Lili Widodo, Head of Fishers Protection Task Force, Directorate General of Capture Fisheries, MMAF

Key Challenges and Findings

One of the key takeaways from the webinar was the need for a suitable vessel registration process for small fishing fleets. By seizing the process and offering incentives for registration, formally recorded and registered to unlock opportunities (as in line with the Principle 1 and 9 of the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency). Many fishers were perplexed as to where to start the process due to bureaucratic hurdles, thus Pesisir Lestari (YPL) initiated a pivotal step for the fisher community in Luwuk Regency together with local authority to open registration and vessel-measurement booths to provide direct access for fishers. Paralelly, a human rights and social responsibility training was conducted for the fishing communities in Luwuk, Central Sulawesi, to help them navigate the system and take advantage of existing social security programs.

Further, the discussion on webinar highlighted how legal frameworks must be strengthened to accommodate the needs of small-scale fishers, while targeted programs should be designed to facilitate their access to essential social services. Additionally, collaboration with local government and community development programs at the village and district levels will be key to improving fisher resilience and ensuring they are not left behind.

Ensuring social protection for small-scale fishers is not the responsibility of a single entity. It requires coordinated action among policymakers, industry leaders, civil society organizations, and fishers themselves. By working together, stakeholders can create a more resilient and sustainable fisheries sector where small-scale fishers are recognized, protected, and empowered to continue their vital contributions to Indonesia’s economy and food security.

Civil society in Ghana asks new Fisheries Minister to tackle illegal fishing with greater transparency

The Coalition for Fisheries Transparency (CFT), together with local environmental organizations, congratulates Hon. Emelia Arthur on her appointment as Ghana’s new Minister for Fisheries and Aquaculture Development (MoFAD).

In her first week in office, Hon. Arthur presented a bold vision for sustainable growth of the fisheries and aquaculture sector. Among plans, the minister announced: accelerating efforts to lift a second “yellow card” issued by the European Union over the country’s failure to combat illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing; establishing a Blue Economy Initiative; implementing improvements in aquaculture and empowering stakeholders – especially women -, by offering loans so they improve their work.

Hon. Arthur also admitted pressing challenges such as overfishing, illegal fishing, limited funding or insufficient data collection that she committed to addressing during her tenure.

The NGOs are expecting the newly appointed minister to deliver on important policies in the National Democratic Congress (NDC) manifesto on fisheries. Local advocacy groups asked Hon. Madam Arthur to protect coastal communities from the consequences of illegal fishing and associated abuses by adopting the 10 transparency policy principles of the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency during the 2025-2028 mandate.

For Ghana, relevant policy measures to advance fisheries transparency include: regular publication of comprehensive fishing vessel licenses, authorizations, subsidies, official access agreements and sanctions and supplying this information to the FAO Global Record (Principle 2) and making public the information of vessels’ beneficial ownership (Principle 3). By implementing these and other Global Charter principles into law and practice, the improvements will provide fisheries employment opportunities for Ghanaians and support fair and equitable access to fisheries information for coastal communities as well as a voice in decision-making processes.

“As the new Ghana’s Minister for Fisheries and Aquaculture Development, Hon. Arthur is well positioned to provide strong leadership to ensure the sustainable future of Ghana’s coastal communities,” commented Maisie Pigeon, Director for the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency. “Her bold, clear, and transformative vision for the sector’s development builds on important commitments to the transparency made by the country in recent years. Through the adoption of the Global Charter principles, Hon. Arthur has the chance to leverage Ghana’s role in sustainable fisheries governance,” she concluded.

During her meeting with the Fisheries Commission – MoFAD’s implementing agency – last month, Hon. Arthur listed several priorities for the sector, including:

(Source: Republic Online)

- Strengthening the regulation of fishing vessels

- Reducing juvenile fish harvest through trawl sub-sector reform

- Enhancing canoe safety standards

- Monitoring illegal fishing practices with Electronic Monitoring Systems (EMS)

- Establishing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) to conserve marine biodiversity.

Equipped with years of experience in government and development, and with a focus on stakeholder collaboration, Hon. Arthur has the chance to secure the long-term sustainability of Ghana’s fisheries and aquaculture industry.

“Collaboration, innovation, and dedication are key to building a fisheries sector that supports food security, economic empowerment, and environmental preservation,” she emphasized.

Cover image: © Maisie Pigeon

Addressing harm in distant water fishing: a case study from Liberia

Fisheries cannot exist without people. Most of us don’t think twice about the hands that worked hard to get fish onto our plates before we take a bite. For coastal small-scale fishing communities in Liberia, this connection is innate; they depend on healthy marine fish stocks for their livelihoods. However, their livelihoods are currently under threat.

Approximately 58% of Liberia’s four million people live within 60km of the coast. Fisheries in Liberia are a critical source of food and nutrition security, jobs for thousands of Liberians, and a key source of government revenues accounting for around 10% of GDP. However, Liberia’s valuable fishery resources are not just targeted by local small-scale fishers. Foreign fleets seeking access to Liberia’s waters pay fees to the government for the license to fish, a practice known as distant water fishing (DWF).

The first six nautical miles of Liberia’s coastal waters are reserved for exclusive use by small-scale fishers, an area called an inshore exclusive zone (IEZ), where DWF are not permitted. Though this policy has been in place since 2010, local fishing communities continue to struggle, and the full impact of DWF in Liberia is not well understood.

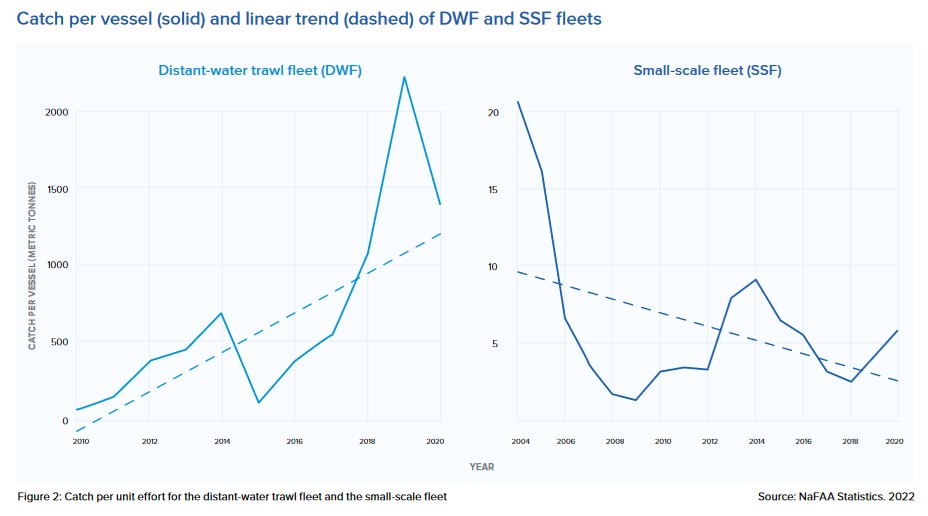

In partnership with the University of Liberia, in 2022 and 2023 Conservation International conducted targeted research on the social, economic and environmental impacts of foreign vessels fishing in Liberia’s waters, with a particular focus on a fleet of trawl vessels flagged to China. The policy brief based on this research provides key findings and recommendations to the Government of Liberia and other relevant actors to safeguard Liberia’s fishing communities and protect its valuable marine resources.

The results indicate that while spatial overlap between the trawlers and small-scale fleets may have been reduced thanks to the inshore exclusion zone (IEZ), the two fleets are still competing for the same resources, to the detriment of local livelihoods and food security. This means that while the IEZ is still a critical management tool for sustainable fisheries and safeguarding coastal livelihoods, on its own, it is insufficient.

The presence of the distant-water trawl fleet in Liberia has significant direct and indirect social, environmental and economic consequences. Governance and management frameworks that prioritize the long-term health of marine ecosystems and safeguard the livelihoods of thousands of Liberians are urgently needed.

To achieve these goals, we’ve outlines three key short-term recommendations:

1. Protect the IEZ: Codify the 6 nautical mile inshore exclusion zone (IEZ) for exclusive SSF access into legislation, rather than executive regulation. Permanent protection for the IEZ will help safeguard coastal community food and livelihood security, but additional government engagement with community members is needed to incorporate local voices into decision- making processes.

2. Invest in SSF sector: Following the FAO’s SSF Guidelines, focusing resources on capacity building for coastal community fisheries, rather than on licensing DWF, may serve to both safeguard the economic, social, and cultural rights of Liberian communities while also maximizing benefits for the government.

3. Increase transparency and equity in decision-making: In line with the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency by the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency, increase access to data and information to improve procedural, distributional, equity in governance. By providing access to data and information, and including coastal community representatives in decision-making processes, Liberia’s government can benefit from the research and analytical support from external groups, and ensure effective implementation of management decisions.

These findings are just one element that support CI Liberia’s Blue Oceans Programme continued efforts for coastal communities, women in fisheries, and local efforts to promote science-based and bottom-up policy reforms with decision-makers that center equity and sustainability over short-term profit.

To learn more, reach out to Katy Dalton, Senior Manager for Distant Water Fisheries (kdalton@conservation.org), or Mike Olendo, Director of Liberia’s Blue Oceans Programme (molendo@conservation.org).

Cover image: © Michael Christopher Brown