Shining a light on Cameroon’s fisheries sector

For more than a decade Cameroon has been in the dark ages with regards to transparency of information on fishing licenses. The Ministry in charge of fisheries has never published information about fishing vessels flying Cameroon’s flag on the ministry’s website. However, in the last two years, things slowly started taking a more positive turn since the country has been regularly publishing the lists of vessels authorized to operate in its waters.

Why the delay in bringing to light such pertinent information?

The rapid expansion of the fishing industry in the last five years caused many African countries, including Cameroon, to face a huge challenge in the management of its fishing registry, fisheries resources, as well as an effective implementation of governance measures, in law and practice. While it is important to undertake transparency measures, emphasis should be laid on the management of fishing activities by government entities, activities of fishing vessels, and traceability of fisheries products, from boat to plate.

Cameroon started publishing the list of fishing licenses in 2023, after the country received a “red card” from the EU for continuous registration of fishing vessels suspected of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing activities, operating outside its waters with insufficient monitoring of their activities.

Transparency measures undertaken by the government of Cameroon

In order to demonstrate strong willingness to improve its behavior, Cameroon has engaged in certain actions with the aim to meet some international transparency requirements such as publicizing its list of fishing licenses on the ministry’s website. One of these actions could be seen in the revision of Cameroon’s fishing law to meet higher international fisheries governance standards. Some principles of the Port State Measure Agreement (PSMA), such as equipping fishing vessels with geo-localization devices and the possibility of institutionalizing an on-board observer program, have been enshrined in domestic law.

In 2023 and 2024, the Ministry of Livestock, Fisheries and Animal Industries (MINEPIA) published its fishing license list as strongly recommended by a non-governmental organization (NGO), the Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF), which has a proven track record in aspects related to transparency and fisheries governance. This publication brought to light 38 fishing licenses issued in 2023 and 39 fishing licenses issued in 2024. The state authority affirms that it is “opting for transparency in the management of fishing activities, monitoring, control and surveillance of its vessels and improving the traceability of fishery products”. The 2023 list was further published on the FAO Global record, a single access point for information on vessels as illustrated in the figure below:

Equally important is bringing out of the shadows the process of vessel registration in Cameroon which is carried out by the Ministry of Transport (MINT). This administration has shown some willingness towards improving things and will be engaged in the development of a digital system. This will enhance traceability and proper monitoring of Cameroon’s fishing fleet, especially IUU fishing fleet flying the country’s flag and operating outside Cameroon’s jurisdiction.

Stumbling blocks to effectively carry out transparency actions

Administrative bottleneck

Validating official documents in Cameroon involves rigorous procedures as many steps have to be undertaken. For instance, the fishery law which has taken many years for its enactment and is still under revision. In addition, this is the case with the MoU document which the government ought to sign with the Global Fishing Watch (GFW), an international NGO dedicated to advancing ocean governance through transparency of human activities at sea. This whole process slows down the development of strategic collaborations.

Insufficient funds

The acquisition of sophisticated technological equipment such as Vessel Monitoring Systems (VMS) & radars to track IUU fishing vessels’ activities entails mobilizing funds, which is challenging, given the country’s limited financial resources.

Insufficient collaboration

The administrations involved in fishery management have not sufficiently put heads together to better manage the fishing industry as is the case with MINEPIA and MINT, as far as fishing vessel registration is concerned.

Towards a more transparent sector

Policy recommendations

Adhering to fishing agreements such as the PSMA, which is the first binding instrument when it comes to IUU fishing, is necessary. Also, the country should adhere to the Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FITI), which comprises transparency requirements for the information that needs to be published by governments. The FiTI supports coastal countries to enhance the accessibility, credibility and usability of national fisheries management information.

Making communication effective

More importantly in addressing transparency in the fishing sector is to explore other avenues to better communicate to the government, general public, the media and coastal communities on issues pertaining to IUU fishing in Cameroon.

The relationship between the FiTI Standard and the Global Charter for fisheries Transparency

A joint statement by the Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI) and the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency (CFT)

Since the Earth Summit in 1992, it has been widely accepted that the equitable and sustainable management of natural resources depends on public access to information. For marine fisheries, however, the call for improved transparency gained momentum much later. Unlike other natural resource sectors (such as oil, gas and mining), governments are only now starting to disclose basic information on their fisheries sector, such as vessel registries, permits, fishing agreements, stock assessments, financial contributions, catch data and subsidies.

This lack of publicly available information does not necessarily stem from a lack of stakeholder demands or regulatory requirements. Many of the elements included in campaigns for transparency in the fisheries sector are already established in international agreements or policy papers on fisheries reforms, such as FAO’s landmark Code of Conduct on Responsible Fisheries or its Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries. Likewise, Freedom of Information laws regularly demand that the public is able to access information held by governments (including on the country’s fisheries sector) with only limited, explicitly defined exceptions arising from confidentiality claims and security matters.

Many fisheries stakeholders regularly promote transparency in fisheries, including intergovernmental organizations such as the UN-FAO, the UNODC, the World Bank, the OECD as well as non-governmental organizations, including small-scale fishing associations or civil society organizations (CSOs). However, it has become evident that in order to motivate, support and monitor governments in providing access to fisheries information, long-term endeavours are needed. In this context, the Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI) and the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency (CFT) were established as two separate initiatives with the objective of improving fisheries transparency.

The FiTI is a global multi-stakeholder partnership that brings together representatives from governments, industrial fishing companies, small-scale fishing associations, civil society and intergovernmental organizations, such as the World Bank, the UN-FAO and the Open Government Partnership. Following a two-year global consultation process, a unique consensus was reached in 2017 on what information regarding marine fisheries management should be published online by national authorities. This consensus is manifested in the FiTI Standard, covering 12 thematic areas of environmental, economic and social aspects of marine fisheries management. Since the FiTI’s legal incorporation as a non-profit organization in Seychelles in 2020 the number of governments implementing the FiTI Standard is steadily growing and strengthening fisheries governance through transparency and stakeholder collaboration. This has resulted in unprecedented access to fisheries information in these countries (including fishing access agreements, vessel registries, stock assessments and license data), increasing public understanding and opportunities for stakeholder participation. As an independent organization, the FiTI also strives to provide clear compliance measures to ensure what governments publish is credible, easy to understand and verifiable.

The FiTI Standard is now widely recognised as a unique global framework that supports national authorities in meeting national, regional and international demands regarding access to information, public participation and fisheries governance. For example, the 79 member States of the Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (OACPS) committed in their prioritised agenda for action (2023-2025) to achieving the highest fisheries transparency standards, and to at least the minimum Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI) standards. Likewise, in a ‘Call for Action’, small-scale fishers from six continents call on their governments to, inter alia, be transparent and accountable in fisheries management by publishing relevant fisheries information to the minimum standards of the FiTI.

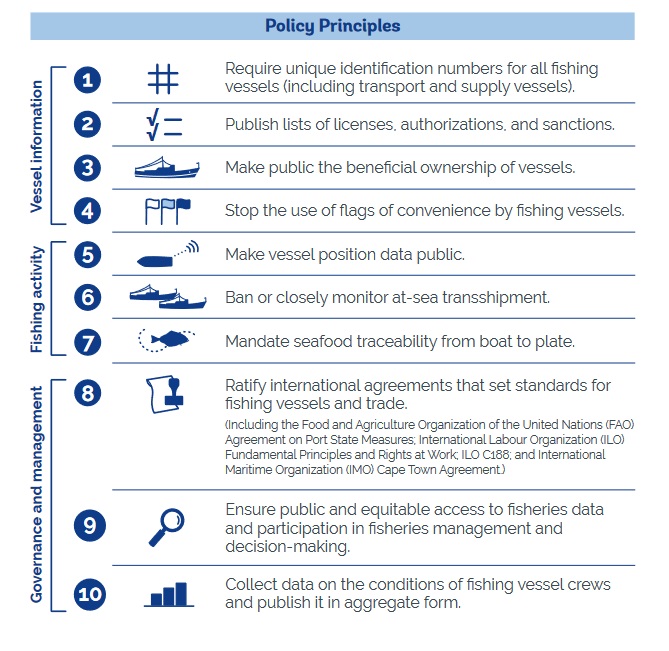

The CFT is a global network of civil society organizations across five continents that work together to improve transparency and accountability in fisheries governance and management. Its Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency’ (short ‘Charter’) was officially launched at Our Ocean Conference in Panama in 2023, following a six-week period of open public comment on the proposed priorities. The Charter is a framework which sets out 10 policy principles developed to support civil society organizations in bringing about effective change in fisheries governance and transparency to support sustainable fisheries, maintain thriving coastal communities, protect crew onboard vessels from human rights and labor abuses at sea and to encourage effective governance. These policy principles seek to address the lack of transparency in three critical areas: vessel information, fishing activity, and governance and management. United around the CFT Charter, the CFT’s members urge governments around the world to adopt the Charter’s 10 principles into law and practice.

The FiTI and the CFT share the common belief that the public availability of information is paramount to achieving sustainable fisheries. Without reliable information the capacity of national authorities to make decisions based on the best available data is diminished. So is the ability of non-governmental stakeholders to exercise effective oversight, demand accountability and engage in public dialogue. Furthermore, both initiatives recognize the benefit of a global alliance of civil society organizations to advocate for enhanced transparency among governments and to utilize published information to hold governments accountable for the benefit of those that depend on a healthy and productive marine environment.

The CFT’s Charter and the FiTI’s Standard have been developed independently with different levels of stakeholder involvement and partially for different purposes. Given that both documents recognize transparency as an important tool to improve fisheries governance, the CFT Charter advocates for the adoption of some policy principles that are already included in the FiTI Standard. This relates to principle 2 on fishing vessel information as well as principle 9 on fisheries data and participation in fisheries decision-making. At the same time, the CFT Charter advocates for requirements that go beyond the purpose of strengthening participatory governance in fisheries, such as targeting illegal fishing or human rights and labor abuses. Hence, several policy principles of the Charter are not part of the FiTI Standard, such as the publication of vessel positions, control systems that ensure seafood is legal and traceable or to stop the use of flags of convenience by fishing vessels.

Despite the differences in how both initiatives were established, as well as the scope of public information they target and their engagement approaches, it is the FiTI’s and the CFT’s shared understanding that both initiatives can work in synergy in promoting transparency for fisheries governance.

- For those governments that are already implementing the FiTI Standard and that are willing to embrace the CFT Charter as well, the Charter’s policy principles 2 and 9 are already met – and even surpassed – given the FiTI Standard’s comprehensive and in-depth approach regarding fisheries management information. Guided by the expertise of local civil society partners, the CFT and its members identify which Charter principles are most vital for governments to adopt and possible to implement. Having these critical principles 2 and 9 established in law and practice facilitates the adoption of the Charter’s additional principles.

- Where governments have embraced the CFT Charter but are not yet implementing the FiTI, CFT supports in creating the enabling conditions by which a government may subsequently become a FiTI country, both by socialising fisheries transparency measures broadly and by specifically advocating for the implementation of the FiTI Standard. The FiTI Standard provides a structured and stakeholder-led framework to ensure that the Charter’s policy principles (i.e. 2 and 9) are met. Crucially, the FiTI Standard is the only internationally agreed framework through which governments can credibly demonstrate their compliance with these two policies of the Charter. This also avoids the risk that national authorities can interpret transparency of fisheries management at their own will and to their own benefit.

Additionally, the FiTI Standard ensures that published government information is useful for non-governmental stakeholders to engage in policy debates, decision-making processes, and exercise oversight, as the FiTI Standard demands the publication of aggregated and disaggregated data for its transparency requirements, including for fishing vessel information and fisheries data (e.g. catches according to flag state, type of fishing gear, etc.). Also, by implementing the FiTI Standard to demonstrate their commitment to the Charter’s principles 2 and 9, national authorities can improve internal data quality and the sharing of information across data silos and identify important data gaps and/to? arrive at stakeholder-agreed recommendations for progressive improvement.

Members of the CFT that operate in countries implementing the FiTI Standard benefit from an independent and globally proven approach to hold countries accountable for their commitment to increasing transparency of fisheries. The FiTI establishes National Multi-Stakeholder Groups in each country (comprising representatives from a country’s government agencies, businesses (industrial and artisanal) and civil society) to ensure that transparency efforts by governments are credible, useful, and sustainable. This provides designated non-governmental stakeholders – such as CSOs and small-scale fishing representatives – with an institutionalised ‘seat at the table’ when it comes to discussing fisheries data and transparency-related actions and policies. CFT’s civil society members can be natural candidates for FiTI’s National Multi-Stakeholder Groups and could therefore play a crucial and active role in the implementation and verification process within their countries. These Multi-Stakeholder Group meetings will also be beneficial to stakeholders to voice concerns, enrich policy development and ensure that measures adopted are well-suited to the unique challenges faced by these stakeholders. Further, CFT members are valuable partners in continuing to hold governments accountable based on the information made public through the implementation of the FiTI Standard.

Advocating for the public availability of critical fisheries information aims to empower governments, civil society, and other stakeholders to engage in informed decision-making, enhance accountability, and foster greater trust in fisheries governance around the world. The ultimate expected impact of fisheries transparency is to enhance fisheries sustainability and pave the way for a healthier ocean, more resilient coastal communities, and a future where the benefits of fisheries are shared equitably.

Ambitious campaign takes on destructive industrial fishing in west Africa

Blue Ventures, a marine conservation organization working to rebuild coastal fisheries and restore ocean life, has launched a three-year project (2024-2027) in West Africa to support the livelihoods and food security of coastal communities against the threats of industrial overfishing.

The region’s small-scale fisheries are increasingly threatened by overfishing by distant-water fleets, whose destructive fishing practices cause devastating, permanent damage to sensitive marine ecosystems and undermine critically important coastal fisheries. Moreover, instead of feeding local communities, much of the catch of the industrial fleet is exported to high-income countries, often without ever making landfall or entering local coastal economies. A large and growing proportion of this catch is transformed into fishmeal and oil to feed high-value fish in foreign aquaculture farms, diverting catches away from local value chains, undermining livelihoods – especially of women – and food security. Added to this, illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing continues to grow, with estimates suggesting that these cost west African economies at least $2.31 billion in annual losses.

The overfishing crisis in west Africa requires holistic and regional solutions. Industrial bottom trawling, pelagic trawling and purse seining all contribute to the overfishing in the region. Effective protection of small-scale fisheries will require not just increased surveillance, but also greater transparency and better fisheries governance by national and regional governments.

The program is led by grassroots national and local organizations working directly with coastal and artisanal fishing communities. It aims to create a regional advocacy network to challenge industrial overfishing and bolster grassroots civil society engagement. The grand kick-off took place at PRCM’s 11th edition of the Regional Coastal and Marine Forum held from 22 to 26 April in the Republic of Guinea Bissau, the largest assembly of marine and coastal conservation stakeholders in west Africa.

Over the next few months and years of the project – that in its first phase includes Senegal, Gambia, Cabo Verde and Cameroon – Blue Ventures hopes to develop tools and information materials to support advocacy efforts, launch national/regional campaigns for better policy development and enforcement against industrial fishing, and ensure sustainable fisheries management through ongoing, coordinated surveillance.

Aissata Dia, Blue Ventures’ advocacy lead in the region, expressed the urgency of this cause: “The activities of industrial vessels are depriving small-scale fishers of their livelihoods and affecting food security in the region. Blue Ventures believes in the power of small-scale fishers to transform coastal conservation, and we place them at the heart of everything we do.”

Collaboration is critical to this initiative. Blue Ventures is partnering with national and local organizations, scientific institutions, NGOs, private sector stakeholders, and technical and financial partners to secure the future of the region’s coastal communities and marine ecosystems.

Ms Aby Diouf, a member of the National Coalition for Sustainable Fishing (CONAPED), expressed her support for the organization’s work in the region, stating: “Thanks to the financial support of Blue Ventures, CONAPED was able to meet the candidates in the senegalese presidential election, including the current government, to encourage them to sign the charter for sustainable fishing. These commitments contributed to the decision to publish the list of industrial fishing vessels authorized to fish in Senegal, which is a major step towards greater transparency in the management of the fisheries sector.”

The inclusion of a diversity of actors in the program offers open and better-informed dialogue among fisheries stakeholders, which in turn provides an opportunity to engage meaningfully in decision-making processes. Blue Ventures hopes this new initiative will significantly and positively impact west Africa’s coastal communities and lead to a brighter, more sustainable future. In the short-run, the organization hopes to encourage the region’s governments to take urgent steps to make transparency in fisheries a reality, by regularly publishing the lists of fishing vessels, joining the Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI) – a global initiative promoting transparency and public disclosure of information on fisheries governance, – and/or by adopting transparency principles of the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency (addressing lack of transparency in three critical areas: vessel information, fishing activity, and governance and management) into law and practice.

A new report demonstrates benefits of transparency in fisheries for governments around the world

The Coalition for Fisheries Transparency calls on states to adopt the principles of the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency into law and practice

A new report A Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency: A framework for collaboration, justice, and sustainability, published today highlights transparency as a powerful tool to improve fisheries governance at the national, regional, and global levels. By publicizing accurate and up-to-date fisheries information, governments can reap an array of benefits, including improving the long-term sustainability of fisheries resources, enhancing food security, ensuring stable livelihoods for coastal fishing communities, fostering inclusive participation in decision-making, strengthening law enforcement, curbing corruption, and preventing human rights and labor abuses at sea.

The report, commissioned by the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency – a global network of civil society organizations that advocate for greater transparency and accountability in fisheries – elaborates on the ten transparency principles in the Global Charter, aimed at addressing some of the most urgent and complex problems in fisheries management, such as overfishing. As of 2021, almost 38% of global fish populations are caught as unsustainable levels, according to the 2024 State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (SOFIA) report, published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

“Several factors contribute to overfishing, including inadequate laws, weak enforcement, and lack of political will. However, one of the most significant causes is the lack of transparency in data on vessel information, fishing activity, and governance and management, which enables illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, as well as a host of other critical challenges,” explained Maisie Pigeon, Director of the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency.

The Coalition’s report outlines each principle and provides recommendations for governments and civil society, demonstrating examples of their real-world application.

“Transparency reforms are urgently needed in fisheries legislation worldwide,” added Pigeon. “By adopting necessary fisheries policy reforms through ten transparency principles of the Charter into law and practice, governments will demonstrate their commitment to equitable, sustainable, and well-governed fisheries that are free from harmful fishing practices, and from human rights and labor abuses,” she concluded.

This entails regular collection, analysis, and public disclosure of data on fishing activities. Moreover, fostering inclusive participation in decision-making processes will allow governments, civil society, industry, and other stakeholders better monitor the use of marine fisheries resources.

Even though the implementation of the Charter principles varies significantly from country to country, the Coalition’s objective is to establish transparency measures by empowering civil society worldwide to catalyze change. Through engagement with governments on fisheries transparency, and strategic prioritization of advocacy efforts, NGOs can drive meaningful progress, ensuring that government decision-making fulfills transparency commitments and addresses the needs of a multitude of actors.

Effective government implementation of global agreements and frameworks is one example of collective action to support the achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG)14 “Life Below Water” before the 2030 deadline. The 3rd UN Ocean Conference in Nice in 2025 represents a critical moment for governments to adopt transparency measures aligned with the principles of the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency. Enactment of these policies will reinforce conference objectives, mobilize collective action, and accelerate fisheries transparency efforts, in turn contributing to the realization of the ambitious goal of SDG14.

Reinforcing Guinea’s fisheries governance through a multi-stakeholder collaboration approach

Multi-stakeholder partnership project

Since 2021, GRID-Arendal, in partnership with Trygg Mat Tracking (TMT), the Regional Partnership for the Conservation of the Coastal and Marine Zone (PRCM), and the Ministry of Fisheries of Guinea (Conakry), has been leading the project Reinforcing Fisheries Governance in Guinea, with generous financial support from OCEANS 5. This multi-stakeholder initiative aims to establish robust sector-specific legislation and support the implementation of effective monitoring and enforcement methods. By engaging local actors in fisheries management and providing training in the use of innovative techniques, the project seeks to improve the management and transparency of Guinea’s fisheries through reforming the sector’s policy framework, enhancing monitoring and reporting of illegal activities, and promoting sustainable fishing practices.

An active engagement of the Guinean government and local stakeholders in policy reform processes constitutes a key component of the project. This includes establishing intra-governmental working groups to strengthen the legal framework, improve monitoring, and increase transparency in the fisheries sector. The project covers two key aspects. The first one aims to enhance inter-agency and multi-stakeholder collaboration leading to the strengthening of policies’ enforcement. The second aspect deals with the use of innovative technology (like Unmanned Aerial Vehicle – UAV and satellite imagery) to overcome surveillance limitations and support existing systems in combating Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) fishing activities.

Improving inter-administration collaboration: a critical overarching approach to building local capacity to fight illegal fishing and increase fisheries transparency

Effective fisheries governance requires a diverse range of stakeholders to coordinate efforts in a harmonious way. Our project, in collaboration with TMT and PRCM, delivered a comprehensive training to local actors responsible for the Monitoring, Control and Surveillance (MCS) of fisheries, enhancing transparency in the fisheries sector by including legal, technical, and procedural aspects.

Workshop in Conakry, Guinea with the agent in charge of the fisheries MCS

Promoting fisheries transparency through an inclusive approach to fisheries management: examples from the Philippines

Aligned with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as part of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and other international agreements, the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency recognizes through Principle 9, the rights to access to information and public participation in decision- making as an essential element for informed policy decisions, and inclusive fisheries management practices. This principle, frames as an essential aspect of fisheries transparency the publication of fisheries management information and the inclusion of diverse stakeholder groups in the decision-making process on fisheries management as follows:

Principle 9: ‘Publish all collected fisheries data and scientific assessments in order to facilitate access to information for small-scale fishers, fish workers, indigenous communities, industry associations, and civil society in developing fisheries rules, regulations, subsidies and fisheries budgets, and decisions on access to fisheries resources. Make these processes, policies, and decisions easily accessible to the public and enforcement agencies.’

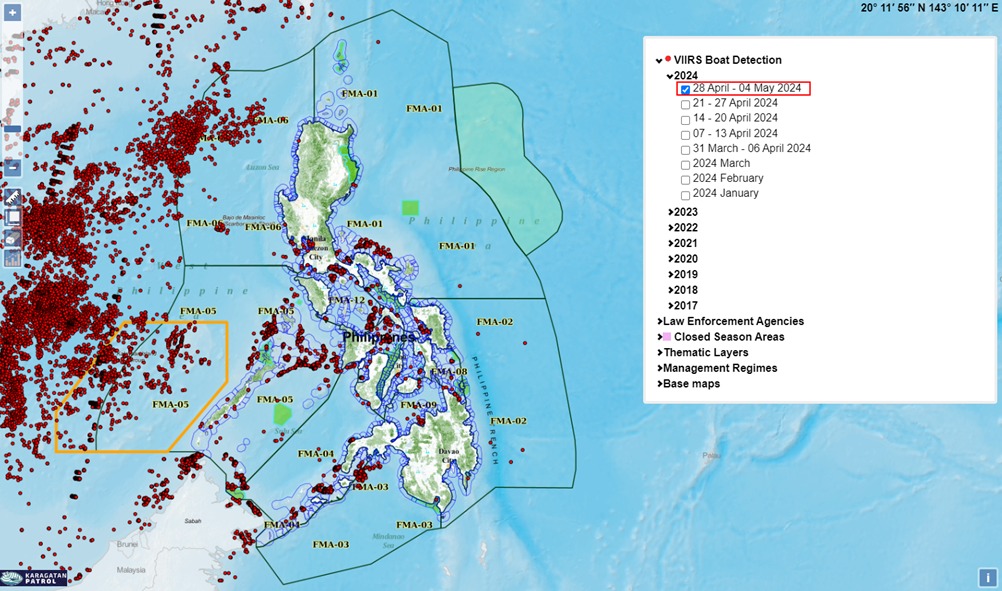

Civil society organizations across the world have implemented mechanisms to promote transparency in the fishing sector through access to information and public participation in fisheries management, as put forth in Principle 9 of the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency. Two examples from the Philippines – the Karagatan Patrol and the Virtual Digital Classrooms – showcase the use of technology, public participation, and collaboration with government agencies in an effort to advance fisheries transparency at a national/regional level.

Karagatan Patrol

Development of the platform “Karagatan Patrol” is an example of collaboration among civil society organizations, government agencies, and coastal communities to collect and manage data. Launched as a nationwide campaign by Oceana in the Philippines to stop illegal commercial fishing in municipal waters, this interactive mapping platform is the result of partnership with the League of Municipalities of the Philippines. The Karagatan Patrol helps report cases of illegal fishing in municipal waters, and disseminates information about potential illegal fishing activities or other environmental violations to the local government, security and enforcement agencies, fisherfolk, industry actors, and media.

KaragatanPatrol.org

Commercial fishing boat detection maps can be accessed by users to demonstrate possible intrusions of commercial fishing vessels in municipal waters. With data analysis from the map, it’s possible for enforcement authorities to detect incidents in municipal waters and prioritize enforcement efforts to report illegal fishing. Additionally, this platform has a Karagatan Patrol Facebook group and a Twitter account, which allow fisherfolk, officers from Local Government Units, members from law enforcement and regulatory agencies to share information, photos, videos, report violations, and ask assistance from law enforcers to report ongoing illegal fishing.

Virtual Classrooms

In 2021, Oceana’s team in the Philippines launched “virtual classrooms” to share information with fishing communities from different parts of the country, with the objective to actively engage them in the decision-making process and fisheries management efforts. The “Classroom for Fisherfolk” learning series aims to gather information from fisherfolk on the 12 Fisheries Management Areas (FMA) system, established in the Philippines’ territorial sea to promote science-based management and address illegal fishing activities. The classrooms, among other things, voice concerns from fishermen and exchange insights with government officials to jointly deal with the challenges raised.

© Oceana /Chris Jude Orbeta

The examples provided by the Karagatan Patrol and Virtual Classrooms in the Philippines demonstrate the critical role transparency, technology, and inclusive collaboration play in advancing fisheries management efforts. By leveraging digital platforms for information sharing, fostering public engagement, and building partnerships with government agencies and coastal communities, these initiatives highlight best practices that can be replicated and adapted by organizations across the world, offering valuable insights and guidance for promoting transparency and inclusion in fisheries management. Through shared knowledge and collective action, it is possible to ensure the responsible use of marine resources and promote the well-being of coastal communities for generations to come.

Monitoring vessels at sea: a crucial first step to achieving transparency in fisheries

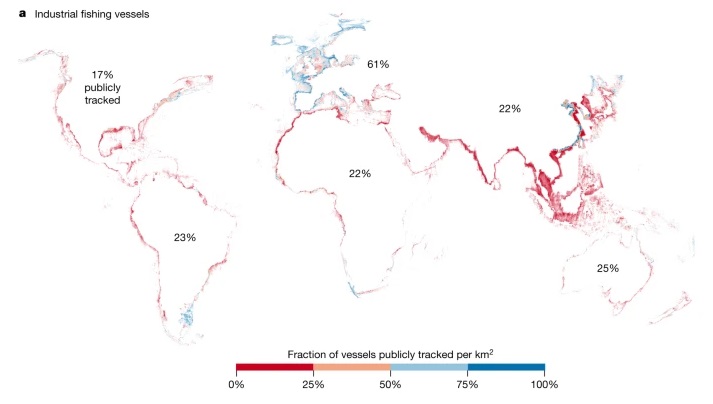

About 75% of global industrial fishing and 25% of other vessel activity is not publicly tracked, asserts the new publication, Satellite mapping reveals extensive industrial activity at sea, issued in Nature with lead authors from Global Fishing Watch – a non-governmental organization that seeks to advance ocean governance through increased transparency of human activity at sea. The findings suggest that these vessels may be at higher risk of participating in illegal fishing activities, like fishing in marine protected areas, or contributing to forced labor or potential human rights abuses.

This also means that our understanding of “who” is fishing “where”, “how” and “in what conditions” the fishing activity occurs, can be limited. As a result, possible negative consequences for coastal communities, marine ecosystems and the global economy are almost impossible to measure.

Over 740 million people depend on the ocean for their livelihoods, nutrition, or both. That creates immense pressure on the ocean, combined with a wide range of harmful human activities that affect its state. Moreover, about a third of fish stocks are fished beyond biologically sustainable levels (threatening the reproduction of fish populations), and an estimated 30–50% of critical marine habitats have been lost owing to human industrialization.

What does public vessel tracking information mean for fisheries transparency?

According to Nature, some of the largest cases of illegal fishing, together with human rights and labor abuses occurring at sea have been committed on vessels that were not using –or required to use- tracking devices. The study revealed that out of the approximately 63,000 vessels detected by GFW between 2017 and 2021, close to a half of them were industrial fishing vessels. Less than 25% of all industrial fishing vessels were publicly tracked, as presented in the following map (adapted from the publication).

When governments do not require the use of tracking devices for fishing vessels or do not make this information public, their vessels cannot be publicly tracked at the level required to effectively manage fishing activities at sea. For example, this research found fishing vessels not publicly tracked inside protected areas, including Galapagos Marine Reserve (~5 vessels/ week) and Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (~20 vessels/week).

What needs to be done?

The Coalition for Fisheries Transparency (CFT) is a global initiative that brings together civil society organizations to promote transparency in the global seafood sector. The coalition’s work is based on the 10 policy principles included under the Global Charter. One of them – principle five – requires governments to mandate the use of vessel tracking devices and make vessel position data publicly available. Sharing vessel tracking data can help reduce the likelihood of labor rights violations, measure the real impact of fishing activity to effectively manage fish stocks, and detect potential illegal fishing activity within marine protected areas. In 2023, CFT organized a regional workshop in Southeast Asia to learn more about members’ concerns around fisheries transparency, current efforts in the region, and opportunities for possible future collaboration with local organizations. Surprisingly, none of the countries in the Asia region currently makes vessel position data from vessel monitoring system (VMS) publicly available, and while data from Automatic Information System (AIS) is public, most countries do not require the use of AIS for all commercial fishing vessels.

Given the pervasive lack of transparency at sea, CFT calls on governments around the world to make vessel tracking systems a requirement, and its data publicly available to effectively monitor vessel activity at sea.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency?

The Coalition for Fisheries Transparency is a network of international civil society organizations (CSOs) that work towards advancing transparency and accountability in fisheries governance and management. United around the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency, Coalition’s members urge governments around the world to adopt its principles into law and practice. The Charter comprises key transparency priorities in fisheries management that must be addressed in order to combat illegal fishing and overfishing, prevent human rights and labor abuses from happening at sea, ensure strong fisheries management, increase equitable participation in fisheries decision-making, and enable thriving coastal communities.

What does the Coalition aim to achieve?

The Coalition for Fisheries Transparency aims to bring about equitable, sustainable, and well-governed fisheries, free from harmful fishing practices and human rights and labor abuses. We do this by connecting and supporting CSOs in their efforts to advance and accelerate fisheries transparency policies around the world.

Who is part of the Coalition?

Members are at the heart of the initiative as they drive the Coalition’s work by identifying the challenges and priorities to advancing transparency in their countries and/or regions. Members are CSOs around the world that work on fisheries policy reforms. A full list of members can be found on the Members page. Guiding the Coalition is a steering committee of civil society organizations, co-chaired by the Environmental Justice Foundation and Oceana,and joined by Accountability.Fish, Global Fishing Watch, Indonesia Ocean Justice Initiative (IOJI), PRCM (The Regional Partnership for the Conservation of the Coastal and Marine Zone), Seafood Legacy, and the WWF Network. Together, representatives from these organizations provide assistance and share their expertise in fisheries transparency to achieve the Coalition’s mission. The Coalition’s Secretariat supplements members’ efforts through assistance in the areas of communications, research and policy analysis, coordination and partnership building, and strategy development. The Secretariat is composed of a director, policy analyst, communications manager, and associate.

What is the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency?

The Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency is a set of 10 policy principles developed to support CSOs in bringing about effective change in fisheries governance and transparency to combat fisheries mismanagement and illegal fishing, and to prevent human rights and labor abuses from happening at sea. The Charter provides a framework for member organizations to urge governments to implement fisheries transparency policy reforms, in law and in practice. While intended for the entire fisheries sector and readily implementable in industrial fisheries, the Coalition acknowledges that some principles in the Charter require further adaptation before they can be effectively applied to all small-scale fisheries.

How does an organization become a member of the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency?

The Coalition consists of voluntary members. Organizations may request to join the Coalition by submitting a Membership Application form in English, Spanish, or French. The Coalition’s Secretariat will review each application and approve or flag the application for further evaluation by the steering committee. If flagged, the steering committee will discuss the application at their next meeting, with a decision on membership made by consensus. The Coalition will provide a response to new member applications within six weeks of submission. To mitigate any potential conflicts of interest, the Coalition does not extend formal membership to governments, industry entities, or CSOs that operate and/or advocate on behalf of commercial industry. However, these stakeholders are welcome to participate in the Coalition as Affiliates and may request to become an Affiliate by submitting this form.

What are the requirements of membership?

Member expectations and requirements can be found in the Membership Handbook and accompanying Code of Conduct.

Is there a cost for Coalition membership?

There are no membership fees.

Are members financially compensated?

Members are not compensated and should disclose any conflict of interest, including financial or other interest that is adverse to the Coalition’s interests or would otherwise interfere with performance in the Coalition.

Can an organization that does not work on all Charter principles still join the Coalition?

The Coalition does not expect members to work on all Charter principles. However, when joining the Coalition, members agree to the Charter in full as its principles serve as the Coalition’s guiding framework.

How is the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency different from other transparency-focused efforts?

A number of organizations and coalitions are already doing important work to increase fisheries transparency through directly partnering with governments, promoting improved management of regional fisheries management organizations, and working closely with industry to enhance their transparency and traceability practices. The Coalition for Fisheries Transparency is adding to these on-going efforts by centering its approach on organizing CSOs, helping them to accelerate transparency policy reforms through government advocacy. The Coalition’s focus on civil society enables the Coalition to complement the efforts of these other initiatives to collectively move the needle forward on transparency in fisheries globally.

How is the Coalition funded?

The work of the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency is made possible thanks to the generous financial support of Bloomberg Philanthropies, Oceans 5, and Oceankind. The Coalition does not accept funding from industry or government sources.

Civil society groups launch Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency at 2023 Our Ocean conference.

The launch of the Charter by the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency lays out a new roadmap to advance marine governance around the world.

PANAMA CITY, Panama, March 02, 2023 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) — The Coalition for Fisheries Transparency – a new international community of civil society organizations – today launched the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency. The Charter pinpoints the most essential policy priorities needed to combat fisheries mismanagement, illegal fishing, and human rights abuses at sea. Experts, ministers, and delegates from international organizations and companies around the world discussed the benefits of the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency at Our Ocean conference in Panama this Thursday and Friday – an annual meeting for countries, civil society and industry to announce significant actions to safeguard the world’s oceans.

“Ghana recognizes the critical role that transparency plays in the fight against illegal fishing to protect livelihoods and provide food security to our coastal communities,” said Hon. Mavis Hawa Koomson, Ghana’s Minister of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development. “With the significant progress Ghana has made in the last year on ending harmful fishing practices that have encouraged illegal fishing in our waters, we are now working towards making greater efforts towards sustaining fisheries transparency in Ghana.”

Prof. Maxine Burkett, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Oceans, Fisheries and Polar Affairs at the U.S. Department of State, highlighted how the U.S. plays a leading role in increasing transparency in global fisheries.

“Last year, President Biden released a National Security Memorandum that recognizes the importance of transparency for combating illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing and associated forced labor abuses,” she said. “By enhancing productive information-sharing, the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency will serve as an important complement to the U.S. government’s activities to end IUU fishing through improving fisheries and ocean governance, increasing enforcement efforts, and raising ambition to end IUU fishing globally.”

Additionally, global partnership initiatives, like the Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI), emphasized the importance of equal, multi-stakeholder collaboration to increase transparency in coastal countries for achieving sustainably managed marine fisheries.

“Given the complexity of fisheries governance, multiple transparency efforts are needed to address the various challenges of unsustainable marine fisheries, such as overfishing, IUU fishing, unequal access to fisheries resources, and unfair benefit sharing,” said Dr. Valeria Merino, Chair of the International Board of the Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI). “The 10 principles of the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency recognize the need for a comprehensive and coordinated approach to fisheries transparency, and has the potential to support existing global endeavors, such as the FiTI, through a much-needed mobilization of civil society organizations to ensure that marine fishing activities are legal, ethical, and sustainable.”

Finally, the role of the civil society to maximize collective impact to improve transparency has been underlined by Mr. Wakao Hanaoka, Chief Executive Officer of Seafood Legacy (Japan), and a steering committee member of the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency. “Our membership in the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency represents a voice of an international community that allows us to strengthen and amplify our efforts amongst the seafood industry and government towards achieving our goal of making Japan a global leader in environmental sustainability and social responsibility,” he explained.

The Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency lays out a new roadmap to advance marine governance internationally, by providing a set of advocacy principles that are both effective and achievable by all stakeholders involved in fisheries governance and management.

“Continuous advocacy efforts by civil society organizations are critical to improving fisheries governance internationally as well as protecting the ocean and the people who depend on its resources,” commented Maisie Pigeon, Director of the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency. “The Coalition’s mission to deliver an urgent shift towards greater transparency in fisheries will be achieved through supporting our members in developing joint strategies, harmonizing and strengthening efforts, and finally – closing transparency policy gaps in fisheries governance,” she concluded.

Through civil society organizations from around the world, the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency calls on governments to apply the Charter’s principles in legislation and practice.

Press contact: Agata Mrowiec agata@fisheriestransparency.net +34 608 517 552